In this page, you can find my published and working papers and book chapters under thematic headings. For description of original data I collected for research, please visit the Data page of this website.

POLITICAL ORGANIZATIONS AND PARTICIPATION IN THE MENA REGION

“What Men Want: Politicians’ Strategic Response to Gender Quotas in Tunisia’s 2018 Municipal Elections” (with Alexandra Blackman and Julia Clark), Comparative Political Studies, 2024

“How do Party Members Respond to Top-Down Moderation: Evidence from the Islamist Party in Tunisia” (with Alexandra Blackman and Julia Clark) – presented at Political Parties in Africa conference, Yale Religion and Politics Conference

“Youth Subcultures and Political Participation in Lebanon and Tunisia” (with Melani Cammett and Sami Atallah)

SECULAR-RELIGIOUS CLEAVAGE IN THE MENA REGION AND BEYOND

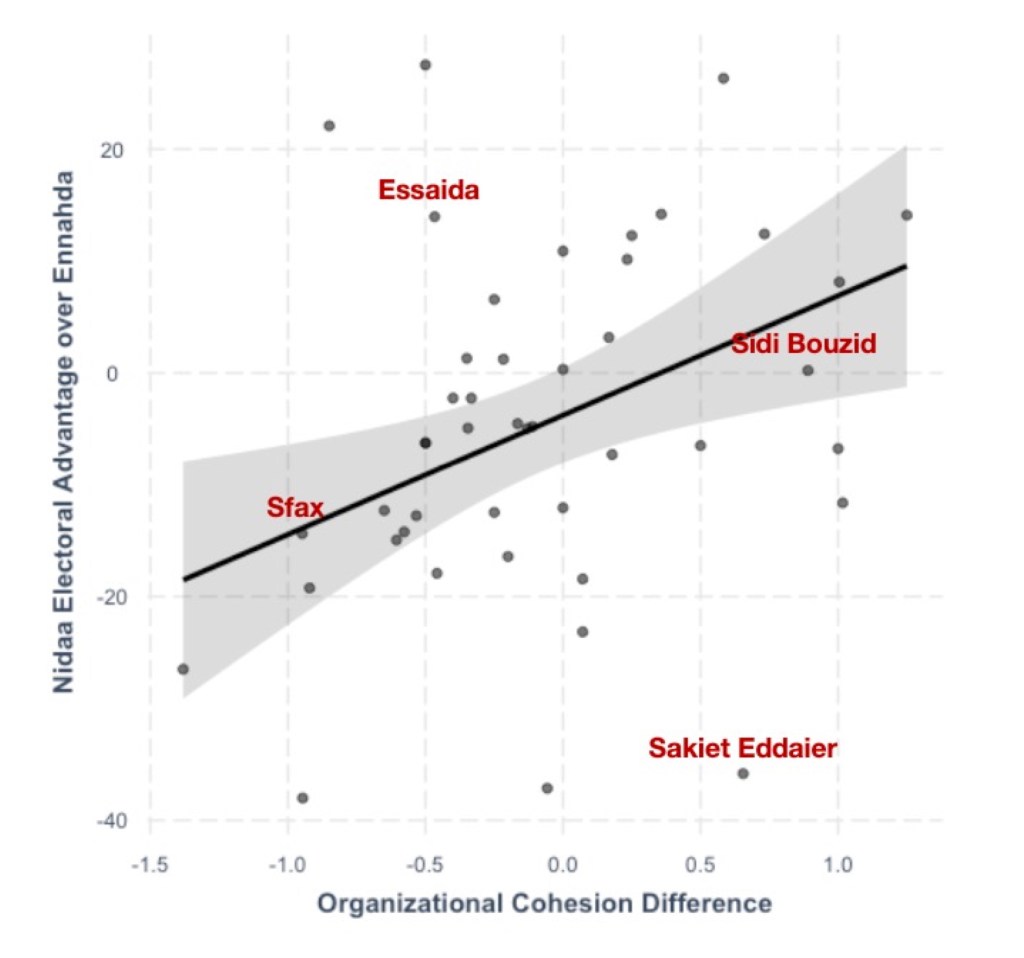

“Unequal Political Selection across Parties: Evidence from the Secular-Islamist Competition in Tunisia” – under review. Winner of 2022 Best Paper Award from the Political Organizations and Parties section of APSA.

“Secular-Religious Party Competition and Conditions of Secular Success: Evidence from Catholic Europe” (with Zeynep Bulutgil) – presented at 2024 CES and 2024 APSA conferences

“Secularism, Religiosity and Regime Preferences in Turkey” (with Tarek Masoud) – presented at 2023 APSA conference and 2023 Penn State Populism and Piety workshop

“The Microfoundations of Power-Sharing Citizen Support for and Opposition to Ethnic Power-Sharing in Lebanon” (with Melani Cammett, Uma Ilavarasan and Sami Atallah) – presented at 2023 MESA and 2024 APSA conferences

LOCAL POLITICS AND DECENTRALIZATION

“Local Political Priorities during Tunisia’s First Democratic Municipal Elections” (with Alexandra Blackman and Julia Clark), in Governance and Local Development in the Middle East and North Africa (Kristen Kao and Ellen Lust, eds.), Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, forthcoming in 2024.

“Political Accountability in New Democracies” (with Chantal Berman, Alexandra Blackman and Julia Clark) – under review [EGAP pre-analysis plan]

“Local Political Dynasties in Turkey” (with Tugba Bozcaga and Rabia Kutlu)

“Electoral and governance outcomes of municipalization of rural governance” (with Esra Bakkalbasioglu, Tugba Bozcaga and Evren Aydogan) [EGAP pre-analysis plan]

SOCIAL SERVICES IN THE CONTEXT OF ETHNIC AND ORGANIZATIONAL DIVERSITY

“Navigating welfare regimes in divided societies: Diversity and the quality of service delivery in Lebanon” (with Melani Cammett), Governance, Vol. 35, 2021.

“Political context, organizational mission and the quality of social services: Insights from the Health Sector in Lebanon” (with Melani Cammett), World Development, Vol. 98, 2017.

“Social Welfare in Developing Countries” (with Melani Cammett), in Oxford Handbook of Historical Institutionalism (Tulia Falleti, Orfeo Fioretos and Adam Sheingate, eds.), New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

“Targeting humanitarian aid using administrative data: model design and validation” (with O. Altindag, S.D. O’Connell, Z. Balcioglu, P. Cadoni, M. Jerneck, A. K. Foong), Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 148, January 2021.

“The IO Effect: International Actors and Service Delivery in Refugee Crises” (with Melani Cammett), International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 66, 2022.

DEMOCRATIC DECLINE AND BREAKDOWN

OP-EDs & BRIEFS

- “CHP’nin Dönüşümünde ve Seçim Başarısında Parti Örgütlerinin Rolü”

Policy brief published by Turkish Foundation for Social, Economic and Political Studies. Also published as a three-part op-ed series at PolitikYol website (1, 2, 3).

- “The Collapse of Tunisia’s Party System and the Rise of Kais Saied” (with Nate Grubman). Analysis piece in MERIP Online. August 2021.

- “Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia is a mosque again. Do Turkish citizens want Erdogan to restore the caliphate?” (with Tarek Masoud). Analysis piece at the Monkey Cage Blog of The Washington Post. July 2020.

- “Who really won Tunisia’s first democratic local elections?” Analysis piece at the Monkey Cage Blog of The Washington Post.

- “One third of municipal councilors in Tunisia are from independent lists. How independent are they?” Democracy International (with Alexandra Blackman and Julia Clark), July 2018. [English] [Arabic]

- “Generational divide in Tunisia’s 2018 municipal elections: Are youth candidates different?” Democracy International (with Alexandra Blackman and Julia Clark), July 2018. [English] [Arabic]

- “List fillers or future leaders? Female candidates in Tunisia’s 2018 municipal elections.” Democracy International (with Alexandra Blackman and Julia Clark), July 2018. [English] [Arabic]

- “Introducing the Tunisian local election candidate survey (LECS): A new approach to studying local governance.” Democracy International (with Alexandra Blackman and Julia Clark), July 2018. [English] [Arabic]